I have always enjoyed learning about the history of astronomy, it is a science whose roots can be traced continuously back to the dawn of human history.

One of my Facebook friends is a bit of an old telescope nut, even more so than myself, regularly posting photos of historic observatories and in particular old refactors. I too have a soft spot for these historic instruments, going out of may way to visit Greenwich Observatory in London, to drive up Mt. Hamilton to see the beautiful old refractor at Lick Observatory, or flying across the country to see one of William Herchel’s telescopes on display at the Smithsonian.

Ovidiu Cotcas recently posted a link to a fun research paper analyzing the telescope optics of Cassinni’s telescopes. These instruments were state of the art in the mid-1600’s, a period when the first telescopes were being used to provide the first good look at astronomical objects, revolutionizing our understanding of the universe. Only five decades after Galileo astronomers across Europe were attempting to build ever better instruments to provide views of the planets that had only recently been nothing but moving lights in the heavens. These early telescopes showed that planets were worlds, opening a whole new realm to observation and study.

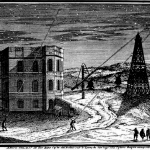

The long focal lengths of those first singlet lens telescopes appear absurd by modern standards, huge instruments with long tubes suspended from masts or with the objective lenses mounted upon tall towers while the observer and eyepiece were at ground level. Telescopes were thirty or even a hundred feet long. Unlike today’s convention of referring to a telescope’s aperture, telescopes were referred to by focal length. Cassini’s primary instruments had focal lengths of between 17 and 40 feet, with one having the incredible focal length of 150ft! As familiar as I am with using small telescopes I shudder at the challenges of aligning and aiming such an instrument, much less tracking a target across the sky.

Giovanni Domenico Cassini was an Italian astronomer born in 1625. In 1669 he moved to France to help construct the Paris Observatory at the behest of King Louis XIV. He had brought with him an excellent telescope objective made by the Italian optician Giuseppe Campani which he used to discover the Great Red Spot, a storm in Jupiter’s atmosphere that persists today. Further lenses ordered from Campani were used in the construction of even more capable telescopes.

Among his many accomplishments was the discovery that Saturn’s rings were not continuous, that there are multiple rings. The largest gap in the rings bears his name, the Cassini division. For this and his other discoveries Cassini is still remembered today. The NASA Cassini spacecraft now in orbit around Saturn was named in his honor.

The lenses were measured mechanically and tested optically using a Zygo interferometer. The numbers are surprisingly good, these 17th century telescopes were capable of resolving good planetary detail. Reading through the paper the authors lay out in detail the optical analysis with numbers on the optical surface accuracy, figures showing the point spread functions and placing a number on the strehl ratios for each of the five lenses tested. The strehl ratios are shown to be 0.8 for the best of the lenses, where one would indicate a perfect lens, not bad at all!

The quality of the glass was shown to have been a major factor in the performance. While today’s optical glass is effectively flaw free, in the 17th century it was a major problem. The index of refraction varies significantly across the lens betraying poor mixing of the molten glass during manufacture. One of the lenses shows a linear structure in the refractive index revealing efforts to better mix the glass by repeated folding or kneading the glass before cooling. This appears to have been a successful effort as the optical performance of the lens is substantially improved.

The tests also confirmed the extraordinarily long focal lengths of the telescopes built around these objective lenses, two of the lenses test showing focal lengths of just under 150 feet. Old descriptions and woodcut drawings of telescopes 100 feet or more in length are hard to believe, but nevertheless real.

The paper is a wonderful look into the challenges faced by early astronomers. Things that are easy today, such as simply buying nearly perfect optical glass, was then a major problem. The astronomers and the instrument makers of 17th century Europe pushed through the problems and made it happen. Those absurdly long telescopes of Cassini are the direct ancestors of the great 8 and 10 meter telescopes of today. To see the discoveries they made despite such unwieldy instruments is a testament to the spirit of discovery that still drives us.