Two earthquakes of the same magnitude strike our island a month apart. Two events that are quite interesting to us at the observatory. Both about the same magnitude, both occurring deep in the island, one was far more forceful at the telescopes causing some minor damage, the second caused no damage that we have found despite a thorough inspection.

Any strong earthquake is a concern for the telescopes. We need to know immediately just how strong the quake was, how much potential for damage occurred.

The telescopes are precision instruments with many delicate parts. On the other hand earthquakes are common on this volcanic island and we have learned how to deal with the shaking.

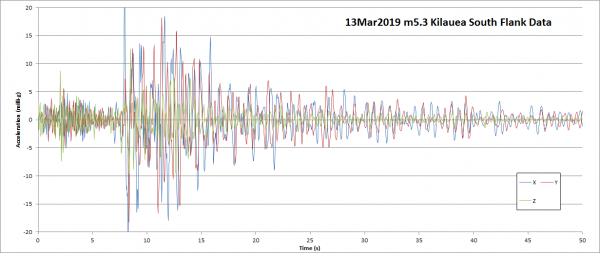

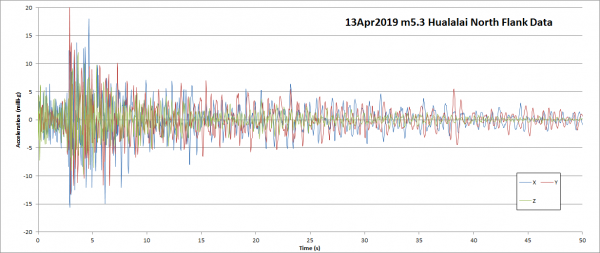

When attempting to measure the possible damage to the telescope it is not earthquake magnitude that is interesting. Rather we want to know the peak ground accelerations that occur at the summit facility. The actual forces that could potentially cause damage. These are measured by means of a logging accelerometer mounted in the basement of the observatory.

The first earthquake occurred in the early morning hours of March 13th while most of the island was asleep. As this quake occurred in the middle of the night both telescopes were operating when it struck. After checking the data from our basement accelerometer it was decided to end observing for the night.

The quake was first reported as a 4.8, later revised to magnitude 5.3, and eventually revised once again to magnitude 5.5 by the USGS after review of the data.

The result was a full day of inspections for the whole crew including myself. The worst of the damage was to the bolts that attach the radial guide pads to the telescope, these large brackets and pads keep the telescope centered in the mount. Each bracket is mounted with four 20mm grade 8 bolts. Bolts as thick as my thumb bent easily by the power of the quake.

It took a long day of work by the crew to put everything right. Our mechanical techs truly outdid themselves and had all of the bent bolts replaced in a few hours.

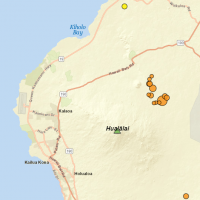

The second quake occurred mid-afternoon April 13th. As it happened in the middle of the day pretty much everyone felt this one, it was the talk of the island for a few days.

At our house is was a pretty good shake, rattling everything and lasting for quite a long time, the better part of a minute. Given that the quake was quite close, the epicenter just a few miles away, the effects were quite memorable from a mild magnitude 5.3 event.

The following day my wife and I were on a snorkel tour to Kealakekua Bay. Talking to island visitors on the boat with us the quake was mentioned in almost every conversation. One eight year old boy excitedly described the quake to me with big eyes, his first earthquake ever.

This second event was almost exactly one month after the first. While the first was deep beneath the flank of Kilauea, this one was deep beneath the volcano of Hualālai. Both quakes are the result of settling as the enormous mass of the volcanoes press against the ancient sea floor and slipping occurs on the boundary.

Despite being closer the Hualālai quake was far weaker at the summit than the March Kilauea event. This can be seen in the two charts included here from our accelerometer. The charts are plotted to the same scale in both force and time.

Interestingly it was the much more distant event that caused the damage. Despite being so similar, the March event delivered much more energy to the summit of Mauna Kea.

The distance to the two events can be seen in the arrival time difference between the primary p-waves and the secondary s-waves. Look at the opening part of the waveform, the period of mild shaking before the arrival of the far more forceful but slower traveling secondary waves.

This time difference allows seismologists to measure the distance to an earthquake. When the distance data from several seismographs is compared the quake epicenter can be plotted for location and depth.

Why the dramatically different amount of energy delivered despite being twice as far away? The answer is most likely in the intervening geology.

Other differences can be seen in the waveforms. The closer quake contains more high frequency components, it appears that distance filters out the higher frequencies. While folks closer to the epicenter reported harsh shaking, further from the epicenters of each quake described it as a rolling motion.

Living on a volcanic island we learn to live with earthquakes, in our homes and around work there are many things we do to prevent damage from these events. The USGS Volcano Observatory website’s earthquake page is bookmarked on so many resident’s computers and phones.

We all become amateur seismologists, many residents can roughly guess the magnitude of a quake from simply the feel of it. We have become earthquake connoisseurs, picking apart the events, the trends, and waiting for the next one.