I have always enjoyed learning about the history of astronomy, it is a science whose roots can be traced continuously back to the dawn of human history.

One of my Facebook friends is a bit of an old telescope nut, even more so than myself, regularly posting photos of historic observatories and in particular old refactors. I too have a soft spot for these historic instruments, going out of may way to visit Greenwich Observatory in London, to drive up Mt. Hamilton to see the beautiful old refractor at Lick Observatory, or flying across the country to see one of William Herchel’s telescopes on display at the Smithsonian.

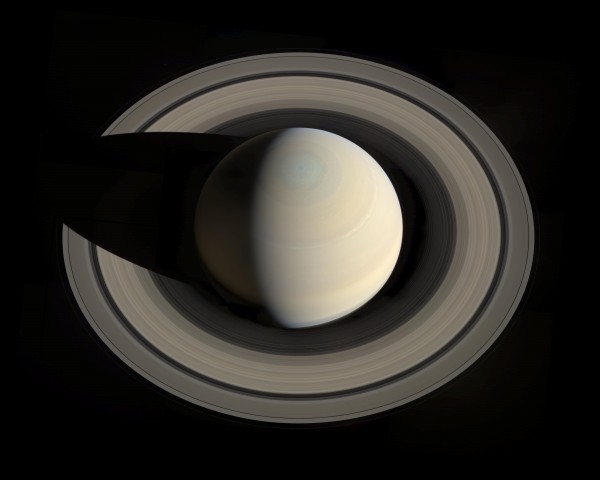

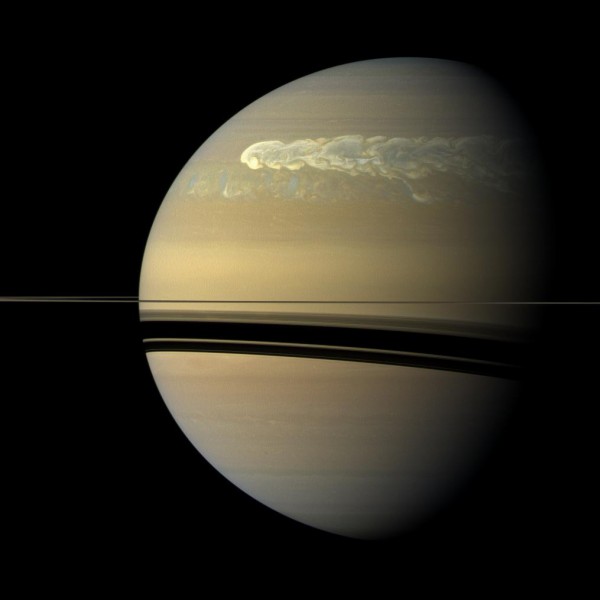

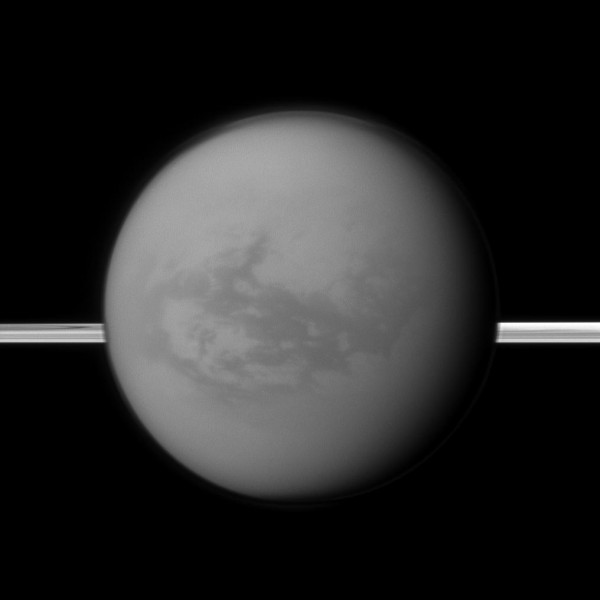

Ovidiu Cotcas recently posted a link to a fun research paper analyzing the telescope optics of Cassinni’s telescopes. These instruments were state of the art in the mid-1600’s, a period when the first telescopes were being used to provide the first good look at astronomical objects, revolutionizing our understanding of the universe. Only five decades after Galileo astronomers across Europe were attempting to build ever better instruments to provide views of the planets that had only recently been nothing but moving lights in the heavens. These early telescopes showed that planets were worlds, opening a whole new realm to observation and study.

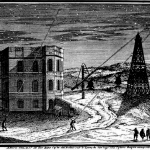

The long focal lengths of those first singlet lens telescopes appear absurd by modern standards, huge instruments with long tubes suspended from masts or with the objective lenses mounted upon tall towers while the observer and eyepiece were at ground level. Telescopes were thirty or even a hundred feet long. Unlike today’s convention of referring to a telescope’s aperture, telescopes were referred to by focal length. Cassini’s primary instruments had focal lengths of between 17 and 40 feet, with one having the incredible focal length of 150ft! As familiar as I am with using small telescopes I shudder at the challenges of aligning and aiming such an instrument, much less tracking a target across the sky.