Most people think that lava flows simply ooze forward and cool in place. But there is more going on than this simple version. Yes, flows ooze forward, but much of the mass of a lava flow arrives later, the flow can inflate to many times the volume as more lava arrives and lifts the crust from underneath.

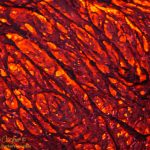

As lava flows forward it can exhibit some very different behaviors. There are two basic forms… Aʻa and pāhoehoe. These two forms of lava flows are easy to spot. Aʻa looks like piles and piles of broken rock, while pāhoehoe appears as a series of smooth mounds, often with a wrinkled surface.

The odd part is that a lava flow may change from aʻa to pāhoehoe behavior and back again as conditions change. The temperature of the lava, the slope, the speed at which it is moving, several variables determine whether you have aʻa or pāhoehoe. The transition is usually quite abrupt with little in-between.

In aʻa lava the crust cools and hardens, then breaks up as the center of the flow continues to move. The result is a moving gravel pile covered in clinkers that range in size from gravel to boulders. The clinkers are usually much lighter than the liquid lava underneath due to the bubbles of gas that make them rather spongy, thus they tend to remain on the surface.

Even once cooled into a thick solid crust the process can continue. As more and more lava arrives under the crust it can lift the crust, inflating the flow to many times the original volume. A flow that started a foot or two thick can become tens of feet deep as this inflation continues.

The video below is a small example of how this happens, showing a small depression being filled with pāhoehoe lava. The camera was set to take a frame every five seconds. These frames are then played at 24fps to compress twenty minutes of time to about ten seconds in this video. Keep an eye to the surface of the flow, behind the red lava, note how it steadily rises as the flow inflates.