A snippet of overheard conversation. I was in Keck 2 control talking with the operator when a few words drifted over the video conference link from Keck 1. Some sort of trouble. I headed for the other end of the building.

Sniffen, our night attendant was looking for the cause of a drive fault. For some reason the computer refused to move the telescope, displaying a drive fault error. It would not move manually either, drive power would not come on. As he explained this to me I was a bit worried. This could be really simple, or really bad. Possibly something that would cost us the night.

Sniffen and I looked at each other… How had the computer driven into a limit? This was not supposed to be possible. While we occasionally put the scope in a limit during maintenance, I had never heard of this occurring during the night. Was it really in the limit? The computer was indicating we were well clear of the limit. Something was lying to us.

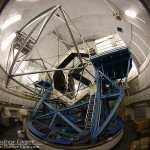

Walking out into the dome and looking up confirmed we actually were on the limit switch. The telescope had driven as far around in azimuth as it could go, stopping just before the hard stop, a massive steel assembly that will definitely stop the telescope.

Oh !#%$! We have to push.

Yes, it is possible to push 300 tons of steel when it is floating on a film of oil. I have never had a chance to do it myself, but years ago someone had shown me how to do it. With Sniffen pressing a pair of pencils into the electrical contactors to release the brakes, I shoved the telescope out of the limit.

It moves surprisingly easy. I had braced my back against the laser enclosure and put my feet against the steel rails used to move the instruments. One good shove and it was moving. I really did not need to brace so well, just a good hard lean against the railings would have done it.

Once you get 300 tons of steel moving, it keeps moving. After I stopped pushing it continued to glide for another few degrees. Low friction creating a clear example of Newton’s first law of motion.

A surreal experience… 2am, in a darkened dome with stars overhead, pushing one of the world’s largest telescopes by hand. Life is interesting sometimes! Twenty six minutes of precious dark lost, but with a quick reinitialization of the telescope we were back on-sky.