Yes… The sky is falling… Literally.

Anyone who spends a good amount of time observing the night sky is well aware of how common meteors are. On any given night you will see five to ten meteors an hour is you observe carefully from a dark site. This rate goes up dramatically during a meteor shower. Most of the meteors you will see are quite small, ranging from dust grains to smallish sand sized bits. Anything large can be quite spectacular. Something the size of a pebble will create a bright meteor, a bright fireball that streaks across the sky.

Estimates vary widely, but something like 50,000 tons of meteoric material rains down on the Earth every year. The process that allowed our planet to form continues to this day.

Occasionally a larger object enters the atmosphere. Something big enough to reach the ground intact. Or even something big enough to cause damage from the impact. How often this occurs would be a surprise to most of our fellow citizens who pay little attention to the the natural world around them.

The Chelyabinsk event got the world’s attention. A medium sized object exploded in the atmosphere directly over a mid-sized city causing modest damage. Due to the prevalence of camera gear in modern Russia we were treated to an unprecedented view of this event. With historical events like Tunguska, all we have is eyewitness accounts and a few grainy black and white photographs of the damage taken years after the impact. Now we get dozens of videos of the event that detail how it occurred from dozens of viewpoints.

While this event is unusual, it was not unprecedented, objects of this size will continue to impact our planet. Meanwhile the event fades from public awareness, at least until it happens again… Which it will.

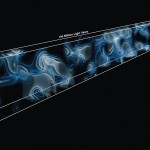

To drive home this point researchers at NASA’s Near Earth Object (NEO) Program have released a map of impacts over the last few years. Using atmospheric sensors that detect the pressure wave of the airburst they were able to locate and estimate the size of the larger events. For further details you can read the press release.

The Chelyabinsk meteor can be seen as a large dot over southern Russia. That event may be the largest dot on the map, but it is not alone. It is the number of other dots that may surprise some people. Our planet is impacted regularly.