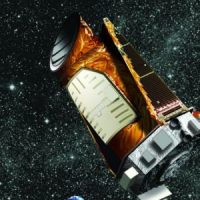

This last week we said goodbye to a truly pioneering space telescope. The Kepler mission was designed to find exoplanets, planets that orbit around other stars. The mission succeeded beyond everyone’s expectations.

After nine productive years this engine of discovery has come to an end. With the spacecraft out of fuel NASA flight engineers sent the last commands, shutting the spacecraft down.

The Keck Observatory and the Kepler Spacecraft had a great partnership. It was not possible to confirm most Kepler’s possible exoplanets using only data from the spacecraft. A large telescope using a high resolution spectrograph, like HIRES on Keck 1, would allow astronomers to not only confirm Kepler’s discovery, but to learn more about each exoplanet.

Using the radial velocity method HIRES data would allow astronomers to pin down the mass of the exoplanet. With the mass of the exoplanet measured it is possible to determine the basic composition, a gas planet like our Jupiter and Saturn, an ice giant like Neptune or Uranus, or a small rocky world more like our Earth. This additional data turned the trove of Kepler discoveries into real information about the universe.

The enormous number of planets discovered by Kepler allows us to start answering some long asked questions… Are planets common around other stars? How many planets are out there? Are there other small rocky worlds, like Earth, where life similar to ours could be found? The key to truly answering these questions is in a large number of samples, provided by Kepler, and statistics and Kepler’s thousands of data points.

Almost every star we see in the sky is likely to have at least a few planets. Somewhere between a quarter and half are certain to have small rocky worlds similar to our own Earth. Planets that are in or near the habitable zone where liquid water could harbor life.

Thanks to the Kepler mission we can confidently answer questions that were total mysteries only a couple decades ago. Questions that lead to one of the most perplexing questions in astronomy… Is there anyone else out there?