W. M. Keck Observatory press release…

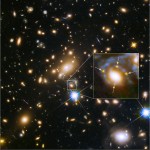

Astronomers have for the first time spotted four images of a distant exploding star, arranged in a cross-shape pattern by a powerful gravitational lens. In addition to being a unique sighting, the discovery will provide insight into the distribution of dark matter. The findings will appear March 6 in a special issue of the journal Science, celebrating the centenary of Albert Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity.

To explain the unique, four-up projection, the scientists determined a galaxy cluster and one of its massive elliptical members are gravitationally bending and magnifying the light from the supernova behind it, through an effect called gravitational lensing. First predicted by Albert Einstein, this effect is similar to a glass lens bending light to magnify and distort the image of an object behind it. The multiple images, arranged around the massive elliptical galaxy, form an Einstein Cross, a name originally given to a multiple-lensed quasar that appear as a cross.

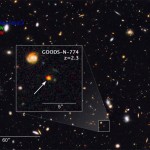

Although astronomers have discovered dozens of multiply imaged galaxies and quasars, they have never seen a stellar explosion resolved into several images. “It really threw me for a loop when I spotted the four images surrounding the galaxy – it was a complete surprise,” said Patrick Kelly of the University of California, Berkeley, lead author of the paper and a member of the Grism Lens Amplified Survey from Space (GLASS) collaboration. The GLASS group is working with the FrontierSN team to analyze the supernova.

Continue reading “Supernova Split into Four Images by Cosmic Lens”