Tag: galaxy

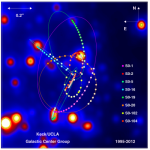

Keck Lecture – Zooming into the Center of our Galaxy

The Galactic Center Group at UCLA has used the W. M. Keck Observatory for the past two decades to observe the center of the Milky Way at the highest angular resolution possible. This work established the existence of a supermassive black hole at the heart of our Galaxy. In this talk, Dr. Leo Meyer, Research Scientist for the UCLA Galactic Center Group, will focus on the black hole itself and the gas that it swallows. The feeding of the black hole is a turbulent process resulting in highly variable emission of infrared light. Observations of this variability provide a great way to learn about the black hole and its immediate environment.

Dr. Leo Meyer – UCLA

May 20, 2014

Show starts at 7 p.m.

Kahilu Theatre, Waimea

Free and open to the Public

Postcard from the Universe – Markarian’s Chain

The center of Virgo is thick with galaxies. The nearest large super-cluster of galaxies lies a mere 53 million lightyears away, includes upwards of 1300 member galaxies and spans over 8° on the sky. The center of the Virgo Cluster is marked by the large elliptical galaxies M84, M86 and M87.

Markarian’s Chain is the long sweep of galaxies stretching from the M84 and M86 pair at the lower right to NGC4477 at the upper left.

UCSC Scientists Capture First Cosmic Web Filaments at Keck Observatory

W. M. Keck Observatory press release…

Astronomers have discovered a distant quasar illuminating a vast nebula of diffuse gas, revealing for the first time part of the network of filaments thought to connect galaxies in a cosmic web. Researchers at the University of California, Santa Cruz, led the study, published January 19 in the journal, Nature.

“This is a very exceptional object: it’s huge, at least twice as large as any nebula detected before, and it extends well beyond the galactic environment of the quasar,” said Sebastiano Cantalupo, first author of the paper and a postdoctoral fellow at UC Santa Cruz.

The standard cosmological model of structure formation in the universe predicts that galaxies are embedded in a cosmic web of matter, most of which (about 84 percent) is invisible dark matter. This web is seen in the results from computer simulations of the evolution of structure in the universe, which show the distribution of dark matter on large scales, including the dark matter halos in which galaxies form and the cosmic web of filaments that connect them. Gravity causes ordinary matter to follow the distribution of dark matter, so filaments of diffuse, ionized gas are expected to trace a pattern similar to that seen in dark matter simulations.

Continue reading “UCSC Scientists Capture First Cosmic Web Filaments at Keck Observatory”

Hubble and Keck Unveil a Deep Sea of Small and Faint Early Galaxies

W. M. Keck Observatory press release…

A team of scientists led by astronomers at the University of California, Riverside has used NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope and the W. M. Keck Observatory to uncover the long-suspected underlying population of galaxies that produced the bulk of new stars during the universe’s early years.

Study results appear in the Jan. 10 issue of The Astrophysical Journal, and will be presented today (Jan. 7) at the 223rd meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Washington DC.

The 58 young, diminutive galaxies spied by Hubble were photographed as they appeared more than 10 billion years ago, during the heyday of star birth.

Continue reading “Hubble and Keck Unveil a Deep Sea of Small and Faint Early Galaxies”

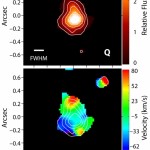

First Detailed Look at a Normal Galaxy in the Very Early Universe

W. M. Keck Observatory press release…

University of Hawaii at Manoa astronomer Regina Jorgenson has obtained the first image that shows the structure of a normal galaxy in the early universe as captured by the W. M. Keck Observatory. The results were presented at the winter American Astronomical Society meeting being held this week near Washington, DC.

These galaxies are known to contain most of the neutral gas that is the fuel for star formation, so they are an important tool for understanding star and galaxy formation and evolution. Discovered and classified over 30 years ago, they have been notoriously difficult to see directly.

Dr. Jorgenson, an NSF Astronomy and Astrophysics Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Hawaii’s Institute for Astronomy, worked with Dr. Arthur Wolfe of the University of California, San Diego. They used the advanced technologies of the W. M. Keck Observatory on Mauna Kea to obtain the first-ever spatially resolved images of a galaxy of this type.

The galaxy was detected with the 10-meter, Keck I telescope fitted with OSIRIS and the Laser Guide Star Adaptive Optics system.

Continue reading “First Detailed Look at a Normal Galaxy in the Very Early Universe”

The Rise and Fall of Galactic Cities

In the fable of the town and country mice, the country mouse visits his city-dwelling cousin to discover a world of opulence. In the early cosmos, billions of years ago, galaxies resided in the equivalent of urban or country environments. Those that dwelled in crowded areas called clusters also experienced a kind of opulence, with lots of cold gas, or fuel, for making stars.

Today, however, these galactic metropolises are ghost towns, populated by galaxies that can no longer form stars. How did they get this way and when did the fall of galactic cities occur?

A new study from NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope finds evidence that these urban galaxies, or those that grew up in clusters, dramatically ceased their star-making ways about 9 billion years ago (our universe is 13.8 billion years old). These galactic metropolises either consumed or lost their fuel. Galaxies in the countryside, by contrast, are still actively forming stars.

“We know the cluster galaxies we see around us today are basically dead, but how did they get that way?” wondered Mark Brodwin of the University of Missouri-Kansas City, lead author of this paper, published in the Astrophysical Journal. “In this study, we addressed this question by observing the last major growth spurt of galaxy clusters, which happened billions of years ago.”

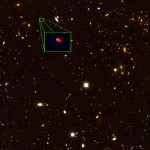

Astronomers Discover Most Distant Known Galaxy

W. M. Keck Observatory press release…

University of Texas at Austin astronomer Steven Finkelstein has led a team that has discovered and measured the distance to the most distant galaxy ever found, using the W. M. Keck Observatory on the summit of Mauna Kea, Hawaii. The galaxy is seen as it was at a time just 700 million years after the Big Bang. The result will be published in the Oct. 24 issue of the journal Nature.

Initial observations from NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope identified many candidates for galaxies in the early universe, but this galaxy is the earliest and most distant definitively confirmed, using the 10-meter, Keck I telescope fitted with Keck Observatory’s newest instrument, MOSFIRE.

Astronomers can study how galaxies evolve because light travels at a finite speed, about 186,000 miles per second. Thus when we look at distant objects, we see them as they appeared in the past. The farther astronomers can push their observations, the farther into the past they can see.

“We want to study very distant galaxies to learn how they change with time,” Finkelstein said. “This helps us understand how the Milky Way came to be.”

The devil is in the details, however, when it comes to making conclusions about galaxy evolution, which means astronomers must employ the most rigorous methods and utilize the most powerful instruments to measure the distances to these galaxies in order to understand at what epoch of the universe they are seen.

The Hubble CANDELS survey uses colors from HST images to identify potentially distant galaxies. Finkelstein’s team selected z8_GND_5296, and dozens of others, for follow-up spectroscopy from the approximately 100,000 CANDELS galaxies. This method is good, but not foolproof, Finkelstein says. Using colors to sort galaxies is tricky because more nearby objects can masquerade as distant galaxies.

In order to accurately determine the distance to these galaxies, astronomers use spectroscopy to measure how much a galaxy’s light wavelengths have shifted toward the red end of the spectrum over their travels from the galaxy to Earth. This phenomenon is called “redshift”, and is due the expansion of the universe.

The team used Keck Observatory’s Keck I telescope in Hawaii, one of the two largest optical/infrared telescopes in the world, to measure the redshift of z8_GND_5296 at 7.51, the highest galaxy redshift ever confirmed. The redshift means this galaxy hails from a time only 700 million years after the Big Bang.

In addition to its great distance, the team’s observations showed that the galaxy z8_GND_5296 is forming stars extremely rapidly — producing stars at a rate 150 times faster than our own Milky Way galaxy. This new distance record-holder lies in the same part of sky as the previous record-holder (redshift 7.2), which also happens to have a very high rate of star-formation.

“So we’re learning something about the distant universe,” Finkelstein said. “There are way more regions of very high star formation than we previously thought. … There must be a decent number of them if we happen to find two in the same area of the sky.”

In addition to their studies with Keck, the team also observed z8_GND_5296 in the infrared with NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope. Spitzer measured how much ionized oxygen the galaxy contains, which helps pin down the rate of star formation. The Spitzer observations also helped rule out other types of objects that could masquerade as an extremely distant galaxy, such as a more nearby galaxy that is particularly dusty.

Other team members include Bahram Mobasher of the University of California, Riverside; Mark Dickinson of the National Optical Astronomy Observatory; Vithal Tilvi of Texas A&M; and Keely Finkelstein and Mimi Song of UT-Austin.

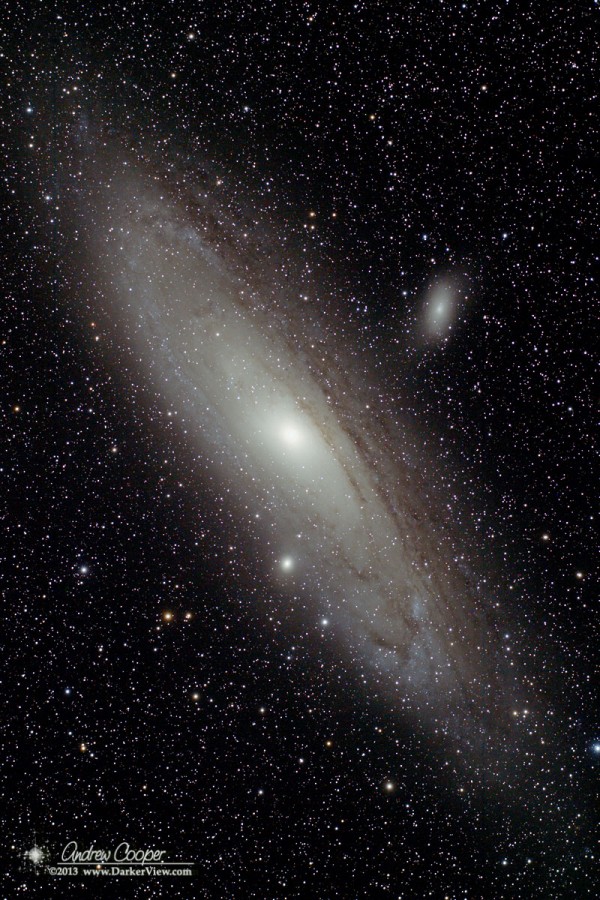

Postcard from the Universe – Andromeda

So I shot M31… yet again. I admit I enjoy this target, it is just so much fun. I always think I can do a little bit better. It is color balance that has been my bugaboo lately, I have really been playing with my technique to achieve a decent color balance. Something aesthetically pleasing and something that bears at least a little resemblance to reality. I understand how objective these criteria are, but still… I try.

Be sure to click on the image to get the large version…