Category: Kilauea

Exploring an active volcano

Lava

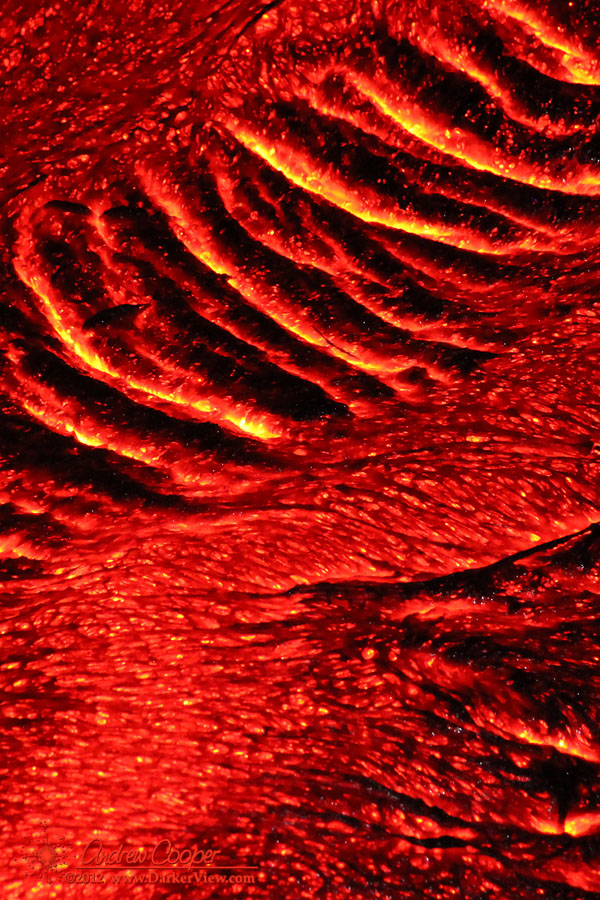

Pāhoehoe Squeeze

Pāhoehoe

Postcard from Hawai’i – Pāhoehoe

Out to the Lava… Again

It was another hike out to see the lava. Not that I really need an excuse to make this hike. This time it was to take a friend along. I have worked with Olivier for several years, between the two of us we do much of the physical maintenance on the Keck adaptive optics systems. Shortly he will be departing the island for another opportunity. Before he leaves he wanted to cross off one more item from his bucket list, seeing the lava close up.

It was still completely dark, the light of the full moon masked by the clouds. The waves were lit by the crimson glow, occasionally surging against the cliffs and hiding the lava from view. The glow also illuminated the billowing clouds of steam rising above each rivulet of lava. The scene is surreal, something that is both unexpected and somewhat difficult to believe. This is something that is outside our usual daily experience.

With the day well begun we headed back to the ocean entry to shoot a few more frames in the early light. We sat on rock that was fairly warm under us, shooting the lava pouring into the waves. Relaxing a bit, digging a few bites to eat from the pack, we talked of cameras and lenses, of life on the island, a last bit of camaraderie with someone I might never meet again. We sat and just enjoyed this spectacle of raw nature. This was why we came, there is some risk in just being here, but the experience is worth it.

Off to See the Lava… Again

Getting to the Lava

Note: This post has been revised based on current conditions and access. You can see the revised post here.

Getting close to flowing lava is a great experience, but one that is fraught with risks. Sometimes the lava is relatively easy to access, near a road or developed trail. Most of the time it takes a serious hike across the old flows to get near, an arduous trip with no trail or map to guide you.

My most recent hike was my fifth trip out to the flowing lava, requiring my longest hike over the flows to date at just under three miles each way. OK, maybe I am not yet a veteran, but these trips have taught me a lesson or two. Going onto the lava is an inherently risky proposition and one must accept that risk. With a little knowledge and preparation the risks can be mitigated. Besides, the reward is spectacular!

You can take my word for it, or perhaps read the same information from someone who has been out far more than I. We will all tell much the same story.

Visiting UAVSAR

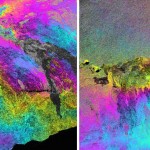

The aircraft is rather unremarkable, a standard small jet sitting among many similar aircraft at the Kona airport. It is the NASA colors and the odd pod hanging underneath that belies that this jet is somewhat unusual. This aircraft does not shuttle passengers across the country, it is home to a unique instrument called UAVSAR.

During this deployment the aircraft has quartered the Big Island, mapping any changes in the landscape on this volcanically active land. The acronym UAVSAR stands for Uninhabited Aerial Vehicle Synthetic Aperture Radar. As the name implies the system is designed to operate from a UAV, but it is currently installed in a crewed Gulfstream III aircraft.

For this mission it is this volcanic island that is the target. As any islander knows we live on a rock that moves. The island settles into the sea, slides into the ocean, and swells where magma pushes its way into the volcano. Each year they return to Hawai’i to re-map the island, this is the fourth year they have returned to check the changes wrought by the volcanoes.

The JPL/NASA folks have completed their mission to the island for the year. Our tour was the morning they were due to depart, flying back to the Dryden Flight Research Center in California.

Hanging underneath the aircraft is the pod containing the radar itself. Bright white, the pod sports a flat antenna down the port side for the sideways looking beam. A trio of scoops on the front ram air through the pod to keep the electronics cool.

We chatted with the flight crew and the radar team learning about the instrument and aircraft. They travel all over the US and sometimes around the globe. They have mapped volcanoes in Alaska and Japan, glaciers in Iceland, measured oil spills, and scanned regions effected by major earthquakes. We noted that they had a fascinating job, while they said the same right back at us.

After the tour our hosts kicked us off the plane and began start-up for their hop back to the mainland. We got the data disks with the GPS data we needed for our tests and traded business cards and contact info. I will have to keep my eye out for the results of this year’s Big Island deployment.