Can anything go smoothly? Please?

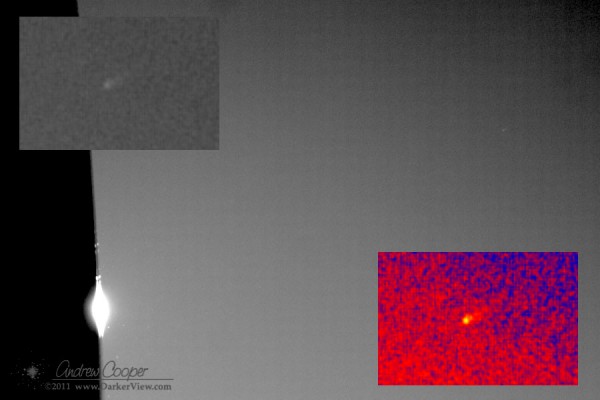

A simple job. Get an 80 pound optical interferometer back under the bench. Nothing like two guys setting the thing on my chest so I can worm my way underneath and heave this beast back onto it’s shelf. Then we have to bolt the fold mirror back in place, another thirty pound piece of awkwardness, just hold it in place to get the bolts in. I hold while Olivier tries to thread the bolts. We also have to replace the pellicle, a bit of ultra-thin optical film that will break if you touch it. Then there is an hour spent aligning the thing. chasing my tail trying to get a properly centered image of the deformable mirror. Sometimes optical alignments just go that way. I finally got a decent image, just to learn there was some vibration in the system. I adjusted some shims to reduce the issue, but there is more to be done.

Much of the remaining day is spent troubleshooting a simple optical shutter in the K1 laser. It fails to completely open. When it fails the safety system detects the failure and shuts down the entire laser. A couple hours of checks later has me convinced that the hardware is working, more or less. The design could have been better. The critical issue is the tight timing requirements. The circuit expects the mechanical shutter to actuate in 50ms, it used to, but as it has been used for a few years, it doesn’t any more. Why they did not simply allow a few hundred milliseconds I have no idea, dumb design, there is no issue with a longer timing window.

There is a camera in the laser enclosure. We use it for tele-presence. As I worked, Pete, our laser engineer, was on the phone assisting from headquarters. He could run the software remotely and watch as I probed the system to measure the timing. Unbeknownst to me, Pete saved a couple images from the camera and sent them to me. The photo does reveal the day I was having. Thanks Pete… I think.